Essays read elsewhere delivered (“nothing but elegy”) a sense for what Hall’s life became after Jane Kenyon. I knew what I was in for. Or so I thought. Fifty four pages into the book, there’s no poetry but a snip from one of hers. There are references to a Donald Hall poetry line now and then, and sometimes a title is given out. But this essay collection – a near-autobiography — is about a life seen almost exclusively from its current vantage point.

After a puzzling bit of naturalist monologue which serves to frame the start and end of this project, Hall wastes no time before announcing that he is no longer writing poetry. He offers tips on writing, revising, on personal pronouns. He casually considers editors past. They seem to have what is now only a distant relevance.

“In my best poems and prose I’ve become steadily more naked, with a nakedness that disguises itself by wearing clothes.”

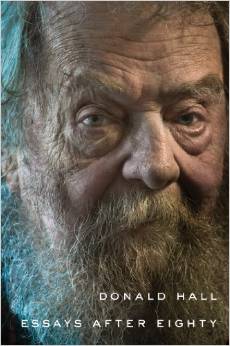

Naked or not, his antiquity screams from the cover photo. But when I read that a National Gallery of Art security guard said to him, “Did we enjoy our din-din?” the humiliation was thorough, humorless. Hall was there in 2011 to receive the National Medal of Arts. (“Wracked with antiquity” or not, at least he fared better when recognized by Philip Roth outside White House security.)

Hall gives us glimpses of other poets of his era — Adrienne Rich and John Ashbery were “classmates at Harvard.” But he dismissively mentions his year as Poet Laureate, “which allowed me more of Washington’s museums.” Poetry is as much profession as art. As he had written elsewhere, he was a freelancer, not a college professor in an MFA program. His essays never veer far from the concrete. There is a chapter on smoking. Truly. An extended riff on beardedness, and its lack.His New England residence is described in detail, the barn . . . and so on. It’s skippable description, save mention of pre-eBook four hundred feet of bookshelves.

A mostly plainspoken Hall is content to reduce poetry to “content,” and to write dispassionately about rejection slips. For him poetry sparks, but it is an obvious combustion. “Really, content is only an excuse for oral sex. The most erotic poem in English is Paradise Lost.” Hall weighs in on the reading styles of Stevens, Elliot, Moore, WC Williams, Dylan Thomas. He talks about being at the Dodge Poetry Festival, which this reviewer attends religiously. He notes with slight interest at the waning reputations of Lowell, Roethke, MacLeish. At times he does so with distressing dispassion.

This is likely intentional.

“Nothing in human life is unmixed.” The self-described antiquity, we learn a few chapters later, was a sturdy 6 foot two when he married a shy 6 foot one Kirby. He could have started with that, of course, but something of the poet remains as he arranges scenes for the reader. Finalities carry their necessary – in Hall’s case, unvarnished — burden: “I survive into my eighties, writing, and oddly cheerful, although disabled and largely alone.”

The book catalogs the frailties, inconveniences, and not only his own. “Friends die, friends become demented, friends quarrel, friends drift with old age into silence.”

What about avid listeners at poetry readings? “They heard lines that resembled poetry.” Rather they had mistaken the tracings and retracings of this first poetry editor at the Paris Review who had sketched out so many versions of his New Hampshire Ragged Mountain that it became poetic.

Advance review copy provided by publisher Houghton & Amazon Vine.