I am naturally attracted to historical fiction, though only an occasional reader of it. In my late 20’s an enormous appetite for science fiction declined. It was replaced, in part, by a greater appetite for nonfiction, but historical fiction received attention, too. Despite that earlier contempt for “what is” and “what has been,” the frameworks provided by properly selected slices of history can be excellent platforms for fiction. A.S. Byatt’s Possession was exemplary in this subgenre.

I am naturally attracted to historical fiction, though only an occasional reader of it. In my late 20’s an enormous appetite for science fiction declined. It was replaced, in part, by a greater appetite for nonfiction, but historical fiction received attention, too. Despite that earlier contempt for “what is” and “what has been,” the frameworks provided by properly selected slices of history can be excellent platforms for fiction. A.S. Byatt’s Possession was exemplary in this subgenre.

When an author accepts such a framework, there are many challenges. Which details should be thoroughly researched so that creativity isn’t mistaken for inaccuracy? Which details should be included and which omitted? How much reader knowledge of time and place should be assumed? What is the current state of scholarship in the era, and what disputes — petty or otherwise — might interfere with the fiction?

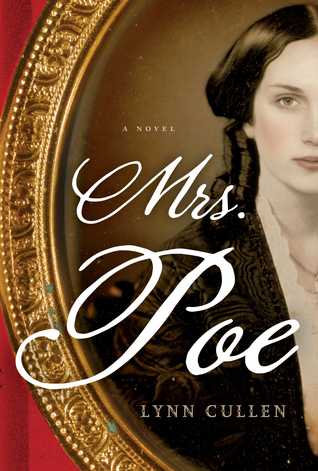

There many other issues not listed here — enough to make the assignment, as another reviewer has written, “daunting.” On the other hand, choosing a cast of characters topped by Edgar Allen Poe, wife Virginia and Frances Osgood and an easily recognized theme — love triangle, of course –would arouse curiosity in ways that an entirely originally plot could not. This was the temptation to which author Lynn Cullen yielded in her novel, Mrs. Poe.

The historical backdrop for Mrs. Poe is deep and recurring, especially in the early chapters. In addition to Edgar and Virginia Poe, readers working out the plot and characters must confront what they already know about John Russell Bartlett, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, William Cullen Bryant, Samuel Morse, Walter Whitman [sic], Herman Melville, T. Roosevelt, Ralph W. Emerson, Sylvester Graham (of “Graham” Cracker fame), Horace Greeley — and more. The novel’s Afterword cites Gotham by Burrows and Wallace (Oxford University, 2000) and The Poe Log by Thomas and Jackson (G,K, Hall, 1987) as inspirational. A serious literary critic of Mrs. Poe would do well to have read both before beginning the novel — simply to avoid the inevitable distractions. It was all I could do to restrain my Wikipedia temptations through the first 14 chapters.

Cullen’s writing is readable and workmanlike. She relies heavily upon dialog passages such as this.

“Perhaps, Mr. Poe,” said Mr. Bartlett, “you should ask her husband.”

My flesh prickled with offensive. “He need not ask Samuel. Samuel would not care.”

Mr. Poe put down the kitten. “I was under the impression that Mrs. Osgood makes her own decisions.”

Mr. Bartlett’s golden brow knotted in disagreement. “I would hope that she would consult her husband on business as well as personal matters. She is a married woman, you know.”

“And as such,” I said, my voice becoming strained,” do my wishes no longer matter?”

“It is the law, Mrs. Osgood,” said Mr. Bartlett.

When the triangle theme became clear early into the novel, I began working on alternate symbols for the title. Beyond the obvious substitution of Frances for Virginia, which Cullen delivers in what was, for me, all-too-literal fashion in Chapter 29, was Mrs. Poe a symbol of a future feminist literati for awkwardly lodged in mid 19th century America? Or was the “Mrs.” in “Mrs. Poe” an ironic counterpoint to the less-than-rigid take on marriage and paternalism voiced by a few of the characters in the novel? It remains an open question at the end.

It is a story about a forbidden love between two — perhaps three — poets. The poetry should carry some of the weight. Alas, my ear for poetry is perhaps too well-tuned to a contemporary American style, and the verse provided by Osgood and the Poes failed to contribute more than a considerable authenticity. Lines like Osgood’s “Thank God for that moment of sweet recognition / That over my heart like the morning light shone!” or Mr. Poe’s “We both have found a life-long love / Wherein our weary souls may rest” are now heard as too earnest.

Cullen has a capable imagination, but the form on this occasion undermined her effort. To be successful would have required much more elevated descriptive writing, less casual dialog and — despite the Poe stereotype — more darkness. The darkness that “made Poe the sexual catnip to the ladies of his time” (from the author’s Afterword) is, to invoke the overused bromide, told not shown. This was not helped by repeated scenes that included Poe’s rescuing a kitten and stroking another while delivering somewhat droll but uninspired lines.

To present a deadlier, more macabre Poe would have been, some would say, inaccurate, oversimplified or both, but it would have been a better read. Cullen may have felt that such a depiction would have been a betrayal of sorts, and the choice of villain in her plot seems to reflect that worry. Yet it remains that a more mysterious, darkly magnetic Mr. Poe — gifted with greater conversational wit than he probably could have mustered given the struggles a real life, doomed Poe faced — would have made Mrs. Poe less realistic and more compelling.

This review first posted on Amazon. Book provided via Amazon Vine.

Mark Underwood writes about knowledge engineering, Big Data security and privacy as @knowlengr and about music and literature as @darkviolin. Also on LinkedIn.