A Review of Aimless Love by Billy Collins

A Review of Aimless Love by Billy Collins

Billy Collins’ pen is a hammer that has been at work building a room for his poems in some pantheon or other. Sometimes that hammer has just the right surface for the nail it wants to hit. Other times, the nail remains unmoved.

For most people, and I count myself among them, this is OK. Collins has singlehandedly enlarged the audience for poetry by eschewing what he calls “gratuitous difficulty” in his own work and insisting on clarity above all else. As he put it in the same interview “. . . I appointed myself the poet who’s gonna feel free to take potshots at the whole enterprise. . . If you find yourself as a writer thinking about posterity you should probably go out for a brisk walk . . . “ He is a defender of humor in poetry, which is doubtless underutilized.

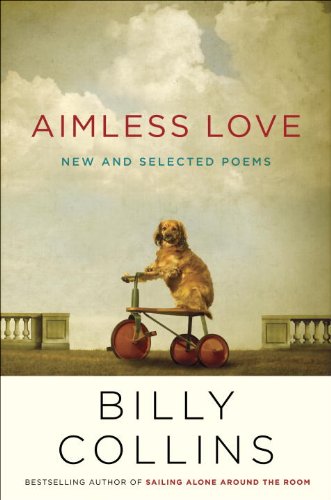

Aimless Love is a collection. (In this choice of title, bear in mind that Collins advised the same interviewer that “I’m speaking to someone I’m trying to get to fall in love with me.”) In addition to new poems, Aimless Love presents work published in Nine Horses, The Trouble with Poetry, Ballistics and Horoscopes for the Dead. I mention this as a purchaser of these previous texts. There is an appreciable per-page value in this collection.

Among the new poems are some that will bring a smile, perhaps against one’s better judgment. For instance, “To My Favorite 17-Year Old High School Girl” both chides and forgives its subject, despite wistful glances at teen overachievers Schubert, Annie Oakley and Maria Callas. In “Lesson for the Day,” Marianne Moore is flattened and left “hanging out to dry.”

There are poems that do not seem to rise above common prose, e.g., “Best Fall” and “Lucky Bastards” seem more like reminiscences. In a not-so-distant past, such efforts would have been tucked into a charming private correspondence.

Given the opinions Collins has voiced about clarity and simplicity, it is ironic that he often chooses topics that mainly appeal to writerly sorts. For instance, he frequently writes about the discipline of writing, or about other poets. In “Dining Alone,” he refers to “Not until I would hear the echo of the front door / closing behind me could I record / in a marbled notebook.” In the fixed-verse send-up “Villanelle,” he pens the self-aware tercet “The first line will not go away / though the middle ones will disappear, / and the third, like the first, is bound to get more play.” Despite this steadfast adherence to offhandness, individual lines vacillate between plain and “poetic” diction, as in “Here and There”:

I feel nothing this morning

except the low hum of the ego

a constant, shameless sound behind the rib cage.

I even keep forgetting my friend in surgery

at this very hour.

In other words, a perfect time to write

about clouds rolling in after a week of sun

and a woman beating laundry on a rock

in front of her house overlooking the sea —

all if which I am making up —

the clouds, the house, the woman, even the laundry.

In contrast to some realist poets who pepper lines with SKUs from Walmart shelves, QwikMart signage and unparaphrased New York Times headlines, Collins uses the everyday sparingly. In this, he is, thankfully, a ruthless editor. Collins insists that readers accompany him on the everyday so that he can trick them into a gentle insight or two. His everyday, we assume, is about writing and speaking engagements and the occasional sipping of wine. So are the poems. In “American Airlines #171,” he offers up an metaphor, then gently undresses it:

life’s end just around another corner or two

yet out the morning window

the thrust of a new blossom from that bush

whose colorful name I can never remember.

Despite the humility in evidence throughout this collection, there are very successful poems present. Closing out the “new” group is “The Names,” one of the strongest poems Collins has written. A very small taste:

Names written in the air

and stitched into the cloth of the day

A name under a photograph taped to a mailbox.

Monogram on a torn shirt,

I see you spelled out on storefront windows

And on the bright unfurled evening of this city.

I say the syllables as I turn a corner –

Kelly and Lee,

Medina, Nardella, and O’Connor.

The proper nouns in the poem take on a lilt and sibilance. It produces just the right commemorative effect. This is an unforgettable poem.

Collins is a steady presence these days. At the time of this review, he can be heard substituting for Garrison Keillor’s regular readings in The Writer’s Almanac. At the same time, in a pantheon somewhere, a person having great trouble suppressing a smile will be reading a Collins poem aloud to a loved one.

The intention is anything but aimless.

[An Amazon Vine review]

Readings

Share book reviews and ratings with DV,

and even join a book club on Goodreads.