Writers like Kate Braverman and Ann Michaels demonstrated that it is possible to jump into hyperdrive from poetry to fiction and to preserve the musicality and concision of poetry in a sea of words that is fiction. It seemed fair to anticipate a similar exercise for Jesse Ball’s Silence Once Begun (Pantheon, 2014), but perhaps that was unfair.

Themes from Kafka, and more Kafka than Camus, dominate the novel’s plot. It begins from a personal, and peculiar trauma, but this trauma Ball must believe can only be decoded as symbolic; it receives little direct attention. There is a distant echo of Dostoevsky in Silence. Its characters resist interviews — indeed resist depiction — then (somewhat inexplicably) burst into long narrative stretches that hint at a poet’s blueline.

Yet in some respects, the whodunit aspect of the novel subtracts from its more literary aspects as the novel’s multi-interview structure unfolds. The events depicted or adapted from historical fact seduce the reader’s sense of injustice or simple curiosity. Plot becomes an ungainly, superordinate force.

A comparatively daring element of Silence Once Begun is the first person, and personal narrator-investigator-interviewer. Author Jesse Ball even uses his own name: interviewees occasionally address him as Mr. Ball. This startles, as does the factual back story of Ball’s wife, whose sudden silence he says sparked the narrator’s interest in a story that unfolded in a distant Japanese town. To whom is Ball speaking more than half way through the novel when he / his narrator writes:

Something about the poem that had been written on the photograph of Jito Joo was haunting me. I woke several times. . .[to] a still lake in a country of still lakes and a bright sun overhead. There was no sound, none at all, There was no possibility of sound. I felt in it the silence that had come over my wife — that very silence which seemed to me then to have ruined my happiness. . .

Specious as the narrator’s labors of love over long letters and poems may seem in today’s Twitter-fied climate of compressible communication, readers who persist are rewarded with delicious bits of aphorism and anguish.

. . . You must show her that this is a thing you understand, this silence, even if it means saying things aloud to her that you have said to no one. . . the stretching on seemingly pointlessly, of life, day after day with no one to call it off.

Silence Once Begun spins several threads that converge in the character of Jito Joo — appropriately, both plotter, co-conspirator and fetching lover. Elsewhere Jito Joo makes an observation that reflects an intuition about fiction that increasingly haunts fiction reading as, like Ball’s Joo, (“Have you seen an old woman life me? I have been old a very long time”), I slip into elder reader status. Ball’s Prefatory Remarks say it, too: “The following work of fiction is partly based on fact.”

The third party of my life was where I was told the meaning of my life. One knows the weight of a thing when it is strong enough to bear its own meaning , to hear its own truth told to it and to remain.

Prospective readers would do well to visualize an elderly Frances Nuyen in the role of Jito Joo with flashbacks handled by Lucy Liu. Ball’s Jito Joo writes in a long letter that is lightly hung on a canto frame such advice as they might mysteriously utter:

Such wild notions do very well, but we must be careful.

Because a plot, a skein of events plucked from a larger stream, is nearly always more than can be told in ordinary fiction, with its limited reverbatory range. Jito Joo explains:

These were true things in our life, but empty in the common air.

____

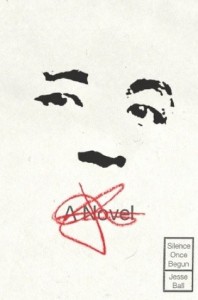

Image credit: Pantheon (@PantheonBooks). Advance review copy provided via Amazon Vine and Pantheon.