There is a mass grave outside Port-au-Prince in Haiti, where, as the Telegraph reported, “some of the more than 220,000 victims of the January 12, 2010 earthquake lie.” As this review is being written, news outlets are doing their best to wrest attention to Haiti from the horror of terrorist attacks on the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, which resulted in the deaths of a dozen French citizens. It is perhaps an understandable challenge.

One might theorize a similar struggle when a novelist weighs the benefits of a story set in the Soviet Union of World War II, where perhaps 20 million died (around 8.7 million military deaths), versus a plot based on a modern day serial killer of women responsible for fewer than a dozen deaths. Both are daunting, both must examine the worst and the darkest elements of human character — sanctioned or otherwise — both must deliver sufficient evil to be true to their subjects. But the novelist who chooses the serial killer is likely to be held to a higher standard. The term “prurient” is not typically applied to wartime storytelling.

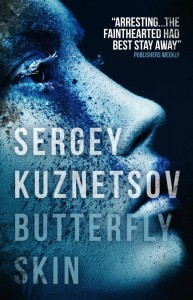

Sergey Kuznetsov’s Butterfly Skin (translated by Andrew Bromfield for Titan Books @TitanBooks) takes on this assignment, with the added difficulty of alternating the narration between perpetrator, victims, acquaintances and business partners. Imagine ending the first chapter with

Days like this are excruciating for me. In order to cope somehow, I start remembering the women I have killed.

At times Kuznetsov works against stereotype. Where a serial killer must be demonized and made to seem a completely damaged personality existing beneath a veneer of normalcy, with 2.5 kids and a discontented but unobservant wife, he sometimes succeeds in creating a self-aware, articulate agent of intermittent — not unremitting – evil. One able to write

. . . there will always be some do-gooder who will hear the screams and knock on the gate in the tall fence and ask what is going on. . . I would like to take him by the hand and lead him over to where the girl is lying naked, like someone on a nudist beach. She knows she is going to die soon. I would like to tell him to squat down and look into her eyes. That is what terror looks like, I would tell him, that is what despair looks like when it condenses so much that you can touch it. Do not be afraid, touch her hand, touch the slippery watering spheres of her eyes. I will give you one of them as a souvenir, if you like.

But also giving the character broad strokes from the ordinary palette:

When we separated I was 24 and she was 27, but now it seems to me that we were complete children who knew nothing of our own desires and were afraid of our own feelings. I wanted to be a rock star and she wanted to be a zoologist like her mother. She’s ended up as a manager in a large Western firm that produces animal feed. I guess that’s zoology too.

The novel, apparently first published in 2004, contains many passages that will be familiar to Westerners, especially life in web development and web agency firms in the same era. Putin’s there, and Chechnya as is the acceptance and cynicism of Russians, and a lacing of Hollywood (Silence of the Lambs, Terminator, Natural Born Killers. OK, but also Russ Meyers’ Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! with its 79% Rotten Tomatoes positive, prurient rating) that borders on envy if not outright idolatry.

Whether the antagonist’s argument that the erotically self-aware Ksenia, final object of his desires is, as he claims, “. . . my second half, the female hypostasis of the alien who lives in my chest” is effective for readers of the crime genre is unknowable. The texture of Butterfly Skin, unlike its smooth title, is a quilt — and some will say patchwork. There are passages of prose poetry, letters, pulp psychiatry, dialog, business plans and social commentary. To make it all hang together, given the brutality (and, to this Western reviewer’s sensibilities, sometimes sexist) elements, would take a writer at the top of his game, not to mention a steadfast conviction for the novel’s vision.

The novel is recommended for lovers of this genre, and perhaps only them. The reason: its aspiration to somehow transcend erotic idiosyncrasy to lay bare a common fascination with the SexDeath God. Kuznetsov’s God is not the God of Haiti’s earthquake, with its vast maiming and death. It is a God that activates unbidden desires for which no prayers will be spoken.

Writers who accept such assignments must contend with contrary truths. Only the living can enjoy such worship, and not only the males of the species. The SexDeath God must speak with believable realism of torture and yet invoke the recesses of imagination where such worship becomes truly erotic.

She has a nice smile, thinks Alexei, innocent and at the same time somehow . . . And he falls asleep without finding the right word, falls asleep picturing Marina smiling, falls asleep hugging his wife, with his face buried in her hair, gold and silver, gold and silver, ghostly light pouring in through the window.

Image credit: Titan Books. Advance copy courtesy of Amazon Vine and the publisher.